SINGLE-PHOTON SOURCES: Quantum dots may hold the key to secure quantum cryptography

MATTHEW T. RAKHER

Much as the laser dramatically changed the telecommunications industry and led to rapid scientific progress in many fields, a single-photon source (SPS) would push photonics to its fundamental limit—control of single quanta—and lead to major advances. While many of those advances are not immediately obvious, there are even now three uses for an SPS.

First among these uses is in quantum cryptography, which promises unconditionally secure communications.1 Second, an SPS could also be applied to quantum computation following the ingenious scheme of Knill, Laflamme, and Milburn, which requires only a source of indistinguishable single photons, high-efficiency photon detectors, and linear optical elements to carry out such tasks as Shor’s algorithm for factoring large numbers in finite time and Grover’s algorithm for searching an unordered database.2 These algorithms promise to speed up difficult computational problems. Third, an emerging application of an SPS is to drive a different system such as an atom or even a mechanical oscillator.

While these applications, primarily the first two, are driving development of SPSs across institutions, researchers will certainly find abundant unforeseen uses for these sources.

Possible candidates

There have been several proposed sources of single photons and many proof-of-principle demonstrations in many systems. These systems fall into four rough categories. The first two categories are based on attenuated laser pulses and spontaneous parametric downconversion in nonlinear crystals, respectively.

While much research has been put into developing these sources and even implementing them in cryptography schemes, they both suffer from the fact that the emission is inherently classical and composed of a broad distribution of photon numbers, which leads to a non-negligible number of multiphoton events, reducing the level of security in a quantum cryptography scheme. In practice, these events can be reduced by further attenuation, but only at the cost of a reduced bit-rate.

The third category of SPSs uses a collective excitation of a cold, atomic vapor. This technique produces highly indistinguishable photons, but is difficult to implement because it requires trapping and cooling of the atoms, in addition to multiple-pulse laser preparation sequences. The probabilistic nature of creating the excitation, as well as the lack of optical confinement, has limited the largest single-photon rate to 100 s.1

The fourth category of SPS is based on a single quantum emitter like an atom, molecule, defect color center, or quantum dot. These sources rely on the fact that when these optically active emitters are excited, they decay primarily by the emission of a single photon. A wide range of these types of sources have been demonstrated, including single molecules, single atoms trapped in cavities, single self-assembled quantum dots, single nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond, and recently single carbon nanotubes.3

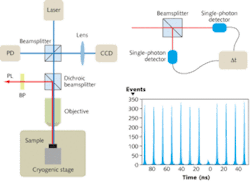

The primary limitation and difficulty in working with these systems is the ability to observe and collect emission from a single emitter. Typically, this task is performed in condensed matter systems with microphotoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy, which uses a combination of spectral filtering and confocal microscopy techniques to eliminate emission from nearby emitters (see Fig. 1, left). The emission is then analyzed using a Hanbury-Brown and Twiss (HBT) interferometer to verify single-photon emission (see Fig. 1, right).

Quantum dots take the lead

Self-assembled quantum dots (QDs) have emerged as a very attractive candidate because of the ease of incorporating them into existing optoelectronic semiconductor technology. In addition, QDs have a near-perfect quantum efficiency and fast, 1 ns radiative lifetime at low temperature. Quantum dots can also be excited nonresonantly by carrier relaxation from nearby quantum wells or from the bandgap of the host semiconductor. Proof of single-photon emission in QDs was first demonstrated in 2000 using a low density of cadmium selenide (CdSe) quantum dots on a glass substrate and since then the field has progressed rapidly. The most commonly used system is composed of indium arsenide (InAs) QDs embedded in a gallium arsenide (GaAs) matrix.

Microcavities benefit QDs

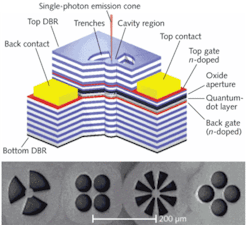

Advances in nanofabrication techniques have led to development of various semiconductor microcavities such as micropillars, microdisks, and 2-D photonic-crystal defect cavities. Embedding the QDs inside a microcavity offers four important and interrelated benefits for their use as single-photon sources. First, the cavity size limits the number of QDs that can participate and effectively acts as a spatial filter that is at least equal to, if not better, than the diffraction-limited spot achieved by a good microscope objective. Second, the small mode volume and high quality factor lead to an increase in the spontaneous emission rate, a phenomenon known as the Purcell Effect. Third, the Purcell effect combined with the small size of the cavity force the single-photon emission dominantly into one mode of the cavity.

The fourth benefit is that, because single-photon emission is now directed into an optical mode of the cavity, it is easier to extract than if it were emitted in all directions. Of course, the ease with which this process is done depends critically on the type of cavity mode, but a tapered optical fiber can be used to efficiently extract photons from the cavity mode in microdisks without introducing significant parasitic loss , and even direct coupling of micropillars to optical fibers has been demonstrated.4

At the University of California Santa Barbara, we recently demonstrated a QD-based SPS with a measured single-photon count rate of 4 × 106 s-1 and a photon capture efficiency of 38% using 80 MHz pulsed excitation.5 This constituted a 20-fold improvement over the previous record 2 × 105 s-1 measured by researchers at Stanford. The mechanism used to achieve this advance was the implementation of intracavity electrical gates to control the charge state of the QD, which prevented formation of the optically dark states that ultimately limit the efficiency of QD-based SPSs (see Fig. 2).Furthermore, the fundamental optical mode of our cavity naturally couples efficiently to our experimental setup due to its Gaussian-like transverse profile. In this way, almost all of the single photons emitted by the QD are directed to the measurement path. Using a similar design, we have also demonstrated fast electrical control of the single-photon polarization with polarization switching rates up to 1 MHz.6

Outlook

There are three natural directions to pursue to improve QD-based SPSs: new cavity geometries, mode-coupling strategies, and changing the way the QD is excited. Recent progress has been made at the University of Texas at Austin using QDs excited resonantly via a laser source that is waveguided perpendicular to the collection direction.7 This is the most efficient excitation mechanism because the carriers are excited directly into the QD rather than having to cascade down. In addition, since each QD has a different emission energy, resonant excitation selectively excites a single QD and reduces background emission.

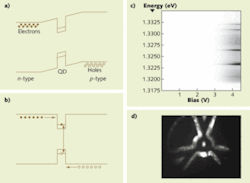

Another approach is to create an all-electrical (“plug-in”) device that would not require an additional excitation laser. This strategy is based on electroluminescence of a quantum dot whereby carriers are electrically injected from nearby charge reservoirs. At its simplest, such a device comprises a QD layer in the intrinsic region of a p-i-n light-emitting-diode (LED) structure. Once the forward bias becomes large enough and current flows through the intrinsic region, carriers can radiatively recombine in the QDs and emit single photons (see Fig. 3). The first such device was demonstrated in 2002 by researchers at Toshiba and recently these LED structures have been combined with micropillar cavities to create an all-electrical SPS operating with a photon capture efficiency of 14%.8 Because of the Purcell effect in these devices, the SPS count rate could in principle increase to more than 1 GHz.Until recently, a further limitation to QD-based SPSs was the degree of indistinguishability present in the single photons. While not important for quantum cryptography, indistinguishability is an important criterion of SPSs for use in quantum computing. Because QDs are embedded within a crystalline matrix, the wavefunctions of carriers are perturbed (dephased) on timescales as short as 100 ps due to interaction with nearby atoms and carriers. This limits the overall coherence length of photons and makes photons from subsequent excitation events distinguishable from one another.

One solution to this problem is to use a cavity to decrease the spontaneous-emission time to roughly the dephasing time—in this way researchers were able to achieve an indistinguishability of 75%.9 More recently, a 64% indistinguishability was demonstrated using electrically generated single photons by a post-selection technique.10

Quantum-dot-based SPSs have made substantial progress over the last few years and remain at the forefront of candidates for use as single-photon sources in quantum information schemes. Future developments should enable creation of single-photon sources capable of gigahertz repetition rates with negligible multiphoton pulses and nearly indistinguishable photons. Such a source will lead to ultrafast bit rates with unprecedented security in quantum cryptography and will provide a necessary component to quantum computation with linear optics.

REFERENCES

- M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000).

- M. Knill, R. Laflamme, and G. Milburn, Nature (London) 409, p. 46 (2001).

- B. Lounis and M. Orrit, Reports on Progress in Physics 68, p. 1125 (2005).

- K. Srinivasan et al., Phys. Rev. A 78, p. 033839 (2008).

- S. Strauf et al., Nature Photonics 1, 704 (2007).

- M.T. Rakher et al., Appl. Phy. Lett. 93, p. 091118 (2008).

- A. Muller, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, p. 187402 (2007).

- D.J. P. Ellis, et al., New J. Phys. 10, p. 043035 (2008).

- S. Varoutsis et al., Phys. Rev. B 72, p. 041303(R) (2005).

- A. J. Bennett et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, p. 193503 (2008).

Matthew T. Rakher is a CNST postdoctoral research associate at the Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899 USA; e-mail [email protected].