SOLID-STATE LASERS: CVD growth methods enable diamond Raman laser

The lure of compact solid-state diamond lasers operating in desirable spectral regions and power regimes, along with numerous other optoelectronic applications, is helping to spur global research and development in industrial diamond fabrication. Enabled by recent advances in chemical-vapor-deposition (CVD) diamond technology, an optically pumped external-cavity CVD-diamond Raman laser has recently been demonstrated by a research team in Australia.

“It’s been known for a long time that diamond was going to be a very good Raman material,” said Richard Mildren, a researcher at Macquarie University (New South Wales, Australia). “But it’s really taken until the past few years for emerging growth methods by CVD to make the material reproducibly at a reasonable cost, such that we can actually do these tests.”

The Raman gain coefficient of diamond is at least 40% higher than alternative Raman materials such as metal tungstates, barium nitrate, and silicon. Diamond also has the largest Raman shift among all of these materials, as well as the largest transparency range, from about 225 nm in the UV to about 100 µm in the far-infrared. And there are numerous spectral regions within that broad range that are not well-addressed by current laser technology, such as yellow for medical applications, a primary motivator for current diamond Raman laser research (www.bioopticsworld.com/articles/342618). In addition, the fact that diamond’s thermal conductivity is about two orders of magnitude greater than most other laser materials offers tremendous potential for high-power laser applications.

Diamond photonic devices

Research into silicon Raman lasers has also generated a lot of excitement because of the potential for optoelectronic integrated circuitry based on current semiconductor technology. Even though diamond lacks silicon’s technology platform for integrated circuitry, during the last decade research interest in integrated monolithic diamond photonic devices has led to laboratory demonstrations of waveguiding, photonic-crystal devices, radiation detection, and photon sources. Such advances have been enabled, by and large, by emerging CVD technology for placing diamond films on silicon substrates.

One research thrust for this technology aims to replace the current 300-mm-diameter silicon-wafer substrate for integrated circuitry with a composite wafer of diamond and silicon having much higher thermal conductivity than pure silicon. An alternative approach hopes to fabricate large single-crystal diamond wafers at affordable prices. Single-crystal diamond films up to 25 µm2 in surface area have become commercially available in the past five years, along with millimeter-size industrial-diamond gemstones.1

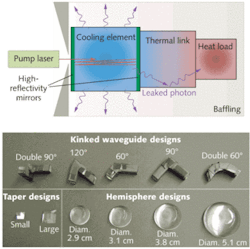

Based on these sorts of material advances, Macquarie University’s Raman laser was built around a 5 × 5 × 1.47-mm-thick uncoated single diamond crystal within a resonator consisting of an input coupler and end-mirror (see figure). The Raman laser was pumped with 10 ns pulses of 532 nm light at a 10 Hz repetition rate from a frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. The researchers achieved a total conversion efficiency of 13% in their external-cavity Raman laser from the pump-signal input to the first Stokes output wavelength of 573 nm.2

Mildren characterized their proof-of-principle demonstration as a relatively crude experiment in which laser efficiency was lessened by numerous correctable factors including lack of antireflective coatings on the crystal faces, residual stress birefringence from the crystal-growth process, and relatively short crystal lengths. The latter two items are already being addressed by ongoing improvements in CVD technology, he added. For instance, in October, Element Six (Ascot, England) announced commercial availability of a CVD diamond for laser applications with a birefringence difference of less than 10-5.

REFERENCES

- P.W. May, Science 319, p. 1490 (March 14, 2008).

- R.P. Mildren et al., Optics Express 16(23) p. 18950 (Nov. 10, 2008).

Hassaun A. Jones-Bey | Senior Editor and Freelance Writer

Hassaun A. Jones-Bey was a senior editor and then freelance writer for Laser Focus World.