Organic electronic devices that can be fabricated on flexible plastic sheets are lightweight and potentially inexpensive to make. Although organic diodes and a few other types of elements have been created, complete organic electronic circuits will require additional components. Researchers at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) have developed an organic electrical bistable device (OBD) that serves as nonvolatile electronic memory; the OBD does not cause self-damage to store bits of information, and is thus long-lived. The researchers then went one step further and integrated organic LEDs into the device.1 The result is a memory that can be read out either optically in parallel or electrically in serial.

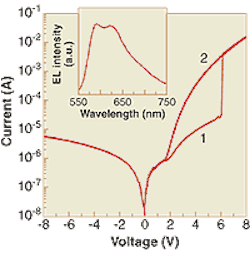

Called an organic bistable light-emitting device (OBLED), the memory unit can be formed either onto glass or flexible plastic substrates. The structure of an OBLED is similar to that of an OBD, with the addition of a vertically integrated organic LED. A typical current-voltage curve for the device shows the bistability required for data storage (left). Applying a reverse-bias pulse nondestructively erases the memory.

Reading data optically in parallel from an OBLED can be done at nanosecond speeds, says Yang Yang, an associate professor at UCLA. When a small reading voltage is applied (lower than the recording voltage), memory elements storing a binary "1" emit an orange glow; a separate optoelectronic system monitors which elements are producing light. The color is not restricted to orange; any color is possible, notes Yang.

A 7 x 7 array of OBLEDs was fabricated on flexible plastic, with each element 0.25 mm2 in area (right). The pixels could be made much smaller, however, says Yang—even down to submicron sizes. Because the light emission is easily visible to the human eye, OBLEDs could also find use as displays for electronic books, newspapers, and signs.

REFERENCE

1.Yang Yang et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. (Jan. 21, 2002).

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.