BIOPHOTONICS: Synthesized nanoparticle taggant is nontoxic

Fluorescent organic dyes have long been used in biological research as tags for molecular diagnostics. But their relatively broad spectral outputs, as well as their short fluorescence lifetimes and tendency to photobleach, have led to much recent interest in quantum dots (QDs) for tagging. But while QDs don’t bleach and have narrow spectral linewidths, they contain metals such as cadmium or selenium and are therefore toxic to the very biological cells and substances under test.

Researchers at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) and Maxim Integrated Products (also of San Antonio) are working with an alternative taggant that is inorganic, like QDs, but is nonpoisonous: rare-earth (RE) nanocrystals.1 They have developed a simple, inexpensive method of fabricating trivalent erbium-doped yttrium oxide (Er3+:Y2O3) nanoparticles; the particles do not photobleach and exhibit narrow spectral lines and long luminescence lifetimes. And unlike QDs, whose wavelength changes with differing particle size, the spectral output of the RE nanoparticles is independent of particle dimensions, allowing the particles to be tailored for different applications without changing their optical characteristics.

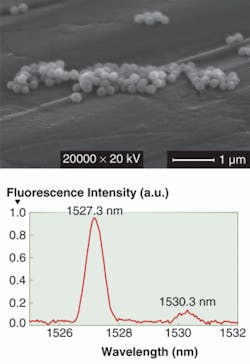

The nanoparticles are created in a bath of salts via a slow chemical reaction; the precipitate is filtered, washed, and dried, then decalcinated (a process in which carbonates and other contaminants are decomposed) at 900°C. The diameters of the resulting Er3+:Y2O3 nanoparticles all lie in a narrow range around 200 nm.

High quantum efficiency

The room-temperature fluorescence spectrum of the RE-doped nanoparticles exhibits a strong line at 1527.3 nm (see figure). The radiative lifetime was calculated to be 48 ms, while the fluorescence lifetime was measured at 45 ms; the resulting quantum efficiency is 99%. The researchers believe that resonant diode pumping the nanoparticles may result in stimulated emission at 1.5 µm.

The simplicity of the fabrication process will make RE-nanoparticle technology more widely available, say the researchers. Similar particles doped with europium (Eu3+:Y2O3) have already been used in biomedical research; for example, a group at University of Turku (Turku, Finland) relies on europium-doped nanoparticles, used in combination with time-resolved fluorometry, to visualize individual biomolecules of prostate-specific antigen.2 However, the erbium-doped particles have advantages.

“Rare-earth-based nanoparticles are becoming the optical taggant of choice because they are nontoxic and highly optically efficient, with detection well separated from the excitation wavelength in the region where tissue and water are transparent,” says John Gruber, a research professor in the physics and astronomy department at UTSA. “While Eu3+:Y2O3 has been shown to be a reasonable optical taggant, our recent work shows that Er3+:Y2O3 is even better, since its fluorescence is at the eye-safe wavelength of 1.54 µm and is 100% efficient in that the transition drops directly to the ground state.” He adds that the particles are photostable materials having surfaces that are well adapted to attach to protein chains by “clathrating” (being held by the proteins as if in a cage).

REFERENCES

1. J.B. Gruber et al., J. Appl. Phys.101, 113116 (2007).

2. H. Härmä et al., Nanotechnology18(7) 075604 (2007)

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.