In November 1967, water flooded into the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, Portugal, coating a collection of 16th-century Islamic manuscripts with mud. Conservators spent years trying to clean the valuable papers and parchments, scraping them and applying chemical solvents. The problem with these methods, of course, is that they not only attack the mud, but they also affect the inks on the documents, and the solvents can sink into the paper or parchment and destroy it.

Fortunately, a better method may exist. Excimer lasers have been used for several years to clean paintings, and recently conservators have tried applying similar methods to documents. Researchers at the Centro de Ciencias e Tecnologias Opticas (Porto, Portugal) and the Instituto Soldadura e Qualidade (Oeiras, Portugal) are trying to determine just what long-term effects laser ablation has on these irreplaceable artifacts.1

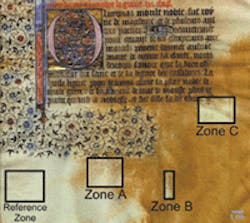

The documents were cleaned with a krypton fluoride laser emitting at 248 nm. The beam was put through a mask with a rectangular slit to cut out the lower-energy portions, then focused through a lens with a 200-mm focal distance, creating a spot on the document of 1.3 x 4 mm. The average energy density delivered was 30 mJ/mm2, and the 170-mJ pulses, at a repetition rate of 9 Hz, lasted on the order of 10 ns each. Approximately 94% of the ultraviolet radiation delivered to the document was absorbed by the mud, exceeding the binding energy threshold of the contaminants and causing the material to break into particles that were blasted away. Each pulse penetrated to a depth on the order of tenths of a micron (see photo).

Researchers Olivério Soares, Rosa Miranda, and José Luis Costa used a spectrocolorimeter with a dynamic spectral range of 400 to 700 nm and a spectral bandwidth of 15 nm (FWHM) to study different areas of the documents. After initial measurements, the documents were placed in a chamber, where the temperature and humidity were held steady and further readings were taken. They looked at different areas of the documents that had been subjected to different numbers of pulses, although they were treated identically otherwise. On the paper, for instance, treatments varied from 2728 pulses in one spot to 7231 in another. On the parchment the range was from 3851 to 12,523 pulses.

Tracking the color values and reflectivity of the documents from Oct. 1996 to Oct. 1998, the researchers found that the parchment showed an initial increase in reflectance and the strengthening of a pale reddish hue. Over time, the reflectance returned to its original value, and the reddish hue faded. The paper became whiter after ablation, but then resumed the aging process, and the colors slowly became more like the colors in the untreated areas. The paper was more sensitive to the cleaning than the parchment, the researchers reported.

Even two years of study is a short time in the life of 400-year-old documents, the researchers point out, and the effects of temperature and humidity need to be studied more closely to get a better idea of the effects of laser ablation. The researchers say they would like to use optical fibers to reduce the size of the area they illuminate, and they are considering using other spectroscopic and luminescence techniques to extend their analysis of both pigments and substrates. A project is underway at Portugal's National Archives, or Torre do Tombo, to study other ancient documents, and the researchers are looking at applying similar techniques to antique ceramics.

REFERENCE

- O. Soares et al., Appl. Opt., 6307 (20 Oct. 1999).

About the Author

Neil Savage

Associate Editor

Neil Savage was an associate editor for Laser Focus World from 1998 through 2000.