If you think it's hard to find and keep good employees, you're not imagining it. The labor crunch is increasingly problematic for the laser and optics industries and, indeed, for most high-technology sectors of the US economy. The Coalition for Photonics and Optics—whose membership includes organizations such as the Laser and Electro-Optics Manufacturers' Association, Optoelectronics Industry Development Association, United States Display Consortium, and Optical Society of America—convened a seminar in Washington on June 19 to examine the problem and potential solutions.

While several seminar speakers offered suggestions for chipping away at the problem, none offered a magic bullet that could cure the labor-supply problem once and for all. In fact, Duncan Moore, associate director for technology at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, warned, "If you think it's hard to find people now, it's not going to get any better."

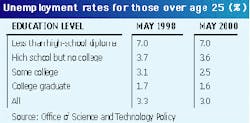

The reason, he said, is that the nation will face an increasing shortage of teachers of math and science, due to the extraordinarily low unemployment rates. According to Moore, among people age 25 and older, the only group with higher unemployment than the national average of 4.1% in May 2000 is made up of individuals who have not graduated from high school—not exactly a prime choice for high-tech employers (see table). Those high levels of employment actually may worsen the labor crunch, he said. "Because the economy is doing so well, people can get jobs in any field no matter what they major in," continued Moore. That situation discourages college students from selecting majors in science and engineering.

Because of the booming economy, students who do major in mathematics or science are unlikely to pursue careers as teachers in elementary or high schools, he said. Consequently, many teachers do not like those fields and may not have excelled in them. According to Moore, that creates one more problem. Those teachers' students may develop a distaste for math and science themselves even before entering college, which would discourage them from taking college-level courses in math and science, much less majoring in those fields.

"If we're going to fix this problem, it's going to have to be way back in the food chain," Moore told the seminar attendees, recommending that company officials work with local school officials to develop curricula in science and math that will entice students—or at least will avoid leaving a bad taste in their mouths. "If we don't start working on the problem today, we're going to be in a worse situation five years out," he continued.

And employers should not expect to look overseas as a solution to their labor problems, other speakers told the conference. The federal government has strict quotas on the number of visas—known as H-1B visas—that it will grant for citizens of other countries to work in the United States in technical jobs. The demand for the visas is much greater than the quota, but proposals for changing the quota are bottled up in Congress, speakers said. "It is an election year, and it is very hard to move things," Sandy Boyd of the National Association of Manufacturers (Washington, DC) told seminar attendees.

Pending legislation

A bill pending in the Senate, S. 2045, would alleviate the problem. It would increase the quota to 195,000 visas annually—not including visas granted to employees of higher-education institutions or nonprofit organizations or visas granted to individuals who have earned a master's degree or higher from a US institution, which would not be counted against the quota. "Estimates are that we have 90 votes for this bill, if we could just get it to the floor," Boyd said. But bringing the bill to the Senate floor is difficult, because many Senators might seek to attach other immigration provisions or even wholly unrelated legislation to the bill.

And even if it passes the Senate, S. 2045 has little prospect of becoming law. Anti-immigration sentiment is much stronger in the House of Representatives, said Michael Aitken of the College and University Personnel Association. "The truth of the matter is that bill could never get through the House," Boyd said.

Two visa bills are pending in the House. One, H.R. 3983, is supported by industry and higher education, because it increases the limit on visas to 200,000 and sets aside 10,000 for higher education and nonprofits. Also, 60,000 of the 200,000 are set aside for individuals with masters degrees or higher from US institutions.

Its alternative, H.R. 4227, is very distasteful to industry and higher education. It would allow unlimited visas to any company that could document a net increase in the median wages paid to its US workers in the previous tax year.

Most likely, Aitken said, the House will craft a hybrid of its two bills, producing something closer to H.R. 3983 than H.R. 4227. But that will happen late this fall, as lawmakers are rushing to leave Washington for the November elections.

In the meantime, Aitken and Boyd both encouraged company officials to contact their representatives and ask them specifically to endorse S. 2045 and H.R. 3983. Moreover, Aitken said that companies should tell lawmakers of the problems that they are encountering. "They don't realize," Aitken said, "that there are positions being unfilled right now."