Spray-on organic image-sensing coating is more efficient than conventional CMOS

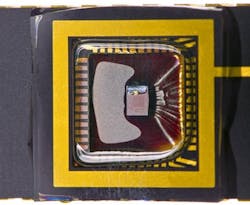

| In tests, organic sensors were up to three times more sensitive to light than conventional CMOS sensors, according to TUM researchers. (Image: A. Heddergott / TUM) |

Munich, Germany--Researchers from Technische Universität München (TUM) have created an image sensor made of electrically conductive plastics sprayed on to the sensor surface of a CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) imager in an ultrathin layer.1 The pixel fill factor is up to 100% higher than for conventional CMOS devices, say the researchers. The chemical composition of the polymer spray coating can be altered so that IR sensitivity is possible, which could enable low-cost IR sensors for compact cameras and smartphones.

The researchers tested spin- and spray-coating methods to apply the plastic in its liquid-solution form as precisely and cost-effectively as possible. They looked for a smooth plastic film no more than a few hundred nanometers thick. Spray-coating was found to be the best method, using either a simple spray gun or a spray robot.

Coating everything, including the electronics

According to the TUM group, organic sensors have already proven their worth in tests, being up to three times more sensitive to light than conventional CMOS sensors, whose electronic components conceal some of the pixels and therefore the photoactive silicon surface.

The organic sensors can be manufactured without the expensive post-processing step typically required for CMOS sensors, which involves for example applying microlenses to increase the amount of captured light. Every part of every single pixel, including the electronics, is sprayed with the liquid polymer solution, giving a surface that is 100 percent light-sensitive. The sensing surface has low-noise and high-frame-rate properties, say the TUM researchers.

While PCBM and P3HT polymers are ideal for the detection of visible light, other organic compounds like squaraine dyes are sensitive to light in the near-IR region.

REFERENCE:

1. Daniela Baierl et al., Nature Communications, doi:10.1038/ncomms2180