Optogenetics recovers memories lost to mice with Alzheimer's disease

Researchers at the RIKEN-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics (Cambridge, MA) used optogenetics—a method for manipulating genetically tagged cells with precise bursts of light—to demonstrate that brain cells can recover memories in mice with Alzheimer's disease-like memory loss. This finding suggests that impaired retrieval of memories, rather than poor storage or encoding, may underlie this prominent symptom of early Alzheimer's, and points to the synaptic connectivity between memory cells as being crucial for retrieval.

Related: Laser-based eye test for early detection of Alzheimer's

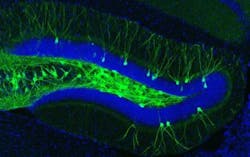

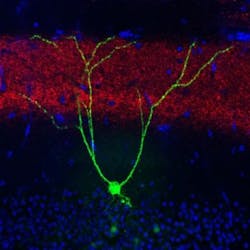

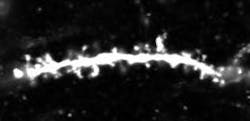

Loss of long-term memory for specific learned experiences is a hallmark of early Alzheimer's disease that is also exhibited by mice genetically engineered to develop Alzheimer's-like symptoms. Building on their previous work that identified and activated memory cells, a group led by RIKEN Brain Science Institute and RIKEN-MIT Center Director Susumu Tonegawa has now shown that spines—small knobs on brain-cell dendrites through which synaptic connections are formed—are essential for memory retrieval in these mice with Alzheimer's. Fiber-optic light stimulation can re-grow lost spines and help mice remember a previous experience.

Mouse memory is often inferred from learned behavior—in this case, associating an unpleasant footshock with a particular cage. Remembering and expecting shocks causes mice to freeze in this enclosure, but not in a neutral one. Compared with normal mice, mice with Alzheimer's exhibited amnesia and reduced freezing behavior, indicating progressive memory loss.

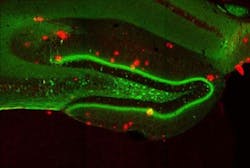

The engrams, or memory traces, of this particular experience are known to be located in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, a key brain area for memory processing. During fear conditioning, researchers used a virus to deliver a gene into the dentate gyrus, which labeled active engram cells. This allowed researchers to visually identify the neurons that made up the engram for that specific fear memory. A second virus contained a gene making only these engram neurons sensitive to light. When the engram cells were reactivated with light in the Alzheimer's mice, memory of the footshock experience became retrievable and freezing behavior was restored.

Memories restored with this method faded away within a day, and the researchers next sought to understand why this happens. They noted a reduction in the number of spines as the mice aged and their Alzheimer's progressed. Their waning memory for the fear training was also linked to a loss of these spines. Previous work had shown that spines grow when neurons undergo long-term potentiation, a persistent strengthening of synaptic connectivity that happens naturally in the brain, but can also be artificially induced through stimulation.

Through repeated stimulation with high-frequency bursts of light to the hippocampal memory circuit in Alzheimer's mice, the team was able to boost the number of spines to levels indistinguishable from those in control mice. The freezing behavior in the trained task also returned and remained for up to six days. The implication is that restoring lost spines in the hippocampal circuit facilitated retrieval of the specific fear experience and its associated freezing behavior.

Optogenetic stimulation did not boost the number of spines in normal mice or strengthen the fear memory, nor did indiscriminately shining light in the dentate gyrus result in any long-term memory improvement. Only the precise stimulation of engram cells was able to increase the number of spines and bring about the memory improvement in Alzheimer's mice.

Tonegawa explains that the ability to retrieve memories in mice with Alzheimer's by increasing the number of spines for normal memory processing only in the memory cells, rather than in a broad population of cells, highlights the importance of highly targeted manipulation of neurons and their circuits for future therapies.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Nature; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature17172.