An invention and patent filing gray area: Obviousness

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary provides some insight into invention. They define “invent” as: 1) to produce (something, such as a useful device or process) for the first time through the use of the imagination or of ingenious thinking and experiment; 2) to devise by thinking.1

In general, this is a pretty good framing of these concepts, although upon re-examination there are some missing elements as far as the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) goes. Let’s explore the statutory, or legal, definition of a patentable invention by the USPTO. This is the definition a prospective inventor’s idea must meet to be issued a patent. The conditions and requirements of U.S. patent laws require an invention to be:

- Useful (utility)

- New (novelty)

- Not an obvious variation of what is known (non-obvious).2

The first two are pretty straightforward, but let’s briefly review the USPTO’s “Big 3.”

Utility. “The requirement for utility is a requirement for a specific and real-world use. An invention must perform its intended purpose. It is not necessary that the invention perform better than existing inventions, but it must be useful in the present day. An incremental step towards future invention or discovery will probably not satisfy the requirement.” This is directly from the statute describing this requirement.2

In reality, utility is the easiest of the Big 3 to meet. For example, let’s take a look at images and drawings of two different fly swatter inventions. My favorite is the October 1994 issued U.S. Patent #5,351,436, “Fly Swatter with Sound Effects.”3 We see a recent image of the invention that can be purchased today on Amazon for $14 to the right, and the utility here is “amusement.” When pesky flies are buzzing around your barbecue with friends, you pull out your fly swatter that enunciates audibles like “gotcha” as you swat that big horsefly on Billy’s forehead. Yep, sure worth $14 on Amazon, you might muse. That’s right—if an invention provides amusement, that is utility enough to qualify for a U.S. patent.

The second fly-wise invention we will take a look at relative to its utility merits is U.S. Patent #7,484,328, “Finger Mounted Insect Dissuasion Device and Method of Use,” issued February 3, 2009.4 Its utility is being a miniature and finger-ring wearable fly swatter. It’s at the ready always, with no need to put down your beer at that barbecue to go on fly patrol! Or is the utility again amusement? Well, whatever it is, it’s good enough for the patent examiners at the USPTO.

Novelty-prior art. A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—1) the claimed invention was patented, described in a printed publication, or in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public before the effective filing date of the claimed invention; or 2) the claimed invention was described in a special (and not very common) USPTO type of issued patent.2

One barometer of whether your idea is novel is to do a quick Google search on the basic terms of the concept and see what pops up. This typically is what most invention review committees around companies do to make a preliminary and first-order novelty search. If it shows up as a product, in a published article, or even in an internet blog, then it is within the public domain and no longer patentable.

Which USPTO invention criteria causes the most difficulty relative to its interpretation? It’s whether an idea or concept being considered for patent filing is “obvious” or not. As cited above, here’s the USPTO’s definition of the criteria:

Non-obvious subject matter. A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.2

My favorite example of something deemed obvious and disallowed for patent issue is from the auto industry during the early part of the 20th century. Ford filed a patent on the curled finger grips it had placed on its automobiles’ steering wheels to improve the driver’s grip while turning the wheel. The USPTO came back and said that was obvious since sword handles had included that feature for quite a long time.

Another example used as an illustration within the USPTO’s own Manual of Patent Examining Procedure is a patent that Ecolab Inc. filed in 2009 for a meat antibacterial treatment with a spray process.5 The differentiating feature of its patent filing was the fact that it claimed an element of the invention was using the spray with “at least 50 psi.” The USPTO found that one skilled in the art of disinfecting meat would adjust the spray pressure to optimally apply a particular solution and typically this was at these claimed pressure levels, so setting the pressure to above 50 psi was obvious to one skilled in the art.

Then, there is the total demolishment of the standard of obviousness via the lobbying of the pharmaceutical Industry. Every new drug patented is allowed another follow-up patent to issue if filed at the end of its 20-year life. The extended-release version of the drug is the basis for the new invention. It’s called patent evergreening.6 With thousands of drugs being issued patents, thanks to this same feature, prior to the latest one, you would think that it would be considered obvious. Nope, it’s now perpetually considered non-obvious. A lesson for inventors as to the power of a good lobbyist in Washington D.C., even within the realm of innovation. When faced with this legitimized dubious course of action, the USPTO has become more lenient relative to many other obviousness determinations. It shouldn’t be ignored by patent seekers within other industries.

The problem with obviousness determinations prior to filing a patent is that they can be quite subjective. One person’s obvious is another’s rejoinder of “well, if it’s so obvious, then why is it novel? No one has done it before for this new or improved utility.” I find myself on the “let’s file” side of this discourse if one other important question is answered in the affirmative. That is, if the patent were to issue, would the invention be of significant economic or strategic importance to the company filing? If that’s the case, then it should be the determination to file for the patent.

I will provide a couple of examples from my own experiences with inventions that were deemed by some reviewing them within the company to be obvious, but were allowed to be filed and eventually issued as patented inventions. See if you agree that they might appear obvious, but in fact these seemingly obvious elements were not deemed such by the USPTO.

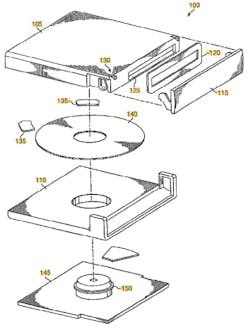

The first example is one at HP while I was on the HP MediaSmart Home Server team in Fort Collins, Colorado, U.S. Patent #7,797,396, issued in September 2010, titled “Network Attached Storage (NAS) Server having a Plurality of Automated Media Portals.”7 This patent describes the inclusion of USB and other types of data ports on the exterior of a headless (no display) computer (home server). It would allow flash keys and other storage device content to be automatically loaded onto the home server via the insertion into the USB connection or similar.

That’s right—putting a USB port on a computer that typically operates without a display. Several people on that patent committee thought obviousness would kill the patent filing in its tracks—but it issued. In this case it wasn’t a market disruptive feature, but a differentiator that HP had exclusivity to while it was in the Home Server market. A footnote to history: HP’s MediaSmart Home Server was the top seller within this market, but this R&D team was disbanded and the product closed out to provide resources for the newly acquired Palm cellular phone product ramp.

Next is an example of a borderline obvious invention I classify as one of my most important economically to my employer at the time. It certainly was not one I would rank among my most insightful or truly innovatively exciting, though. How can this be? The invention, Patent #7,123,446, issued in October 2006, was titled “Removable Cartridge Recording Device Incorporating Antiferromagnetically Coupled Rigid Magnetic Media.”8 It increased the areal density of hard-platter- based removable data storage cartridges by over an order of magnitude! The backstory is that this invention was not for antiferromagnetically coupled media, which was invented a few years earlier by engineers at IBM. After Iomega licensed it from IBM, as all magnetic data storage companies did, and including it in its removable data storage cartridge products, this new combination of elements was patented.

Once the decision was made to license this media technology from IBM for Iomega’s hard-platter removable data storage cartridges, I wrote this invention disclosure with strategic intent. It would be novel. No other removable data storage cartridge had ever had this media type, and the utility was non-negotiable with the >10x areal density increase in removable cartridges. Here was a case where the possible obviousness arguments for not filing for a patent were far outweighed by the value, if issued, of freezing several other competitors within this space out of the market. The revenues increased and protected were significant if it issued—and it did!

Takeaway

The primary takeaway is that if you’re an inventor with an innovative new process, product feature, software utility, or device and your initial instinct is that it was obvious and unworthy of a patent filing, you should pause. You should be mindful of the overriding criteria for the filing of a patent, much bigger than the USPTO’s Big 3 we’ve reviewed. Would the patent, if issued, have an economic or strategic return for you or your company?

It’s within this context that you should consider whether your possibly obvious invention, if a patent were to issue, would be of significant value within the marketplace. If this is the case, then you should file an invention disclosure and advocate not only the novelty and utility of the concept, but even more critically, the exceptional value to your company upon issue. The gray area chasm should be crossed!

It is within all of us to innovate. Today is a good day to file an invention disclosure! Just do it.

REFERENCES

1. “Invention” and “Invent,” merriam-webster.com (Feb. 7, 2022).

2. United States Code Title 35 U.S.C. §101-103.

3. M. W. Spalding and K. J. Spalding, “Fly Swatter with Sound Effects,” Patent #: 5,351,436, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (Oct. 4, 1994).

4. J. R. Daugherty, “Finger Mounted Insect Dissuasion Device and Method of Use,” Patent #: 7,484,328, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (Feb. 3, 2009).

5. Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, “Section 2143 Examples of Basic Requirements of a Prima Facie Case of Obviousness,” U.S. Patent and Trademark Office; see www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2143.html.

6. W. M Spruill and M. L. Cunningham, “Strategies for Extending the Life of Patents,” BioPharm International (Mar. 2005); see www.alston.com/-/media/files/insights/publications/2005/05/strategies-for-extending-the-life-of-patents/files/biopharm-spruill-may2005/fileattachment/biopharm-spruill-may2005.pdf.

7. M. J. Barber, W. G. McCollom, and F. C. Thomas, “Network Attached Storage (NAS) Server having a Plurality of Automated Media Portals,” Patent #: 7,797,396, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (Sep. 14, 2010).

8. F. C. Thomas and D. W. Griffith, “Removable Cartridge Recording Device Incorporating Antiferromagnetically Coupled Rigid Magnetic Media,” Patent #: 7,123,446, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (Oct. 17, 2006).

About the Author

Fred Thomas

Fred Thomas works in HP’s Advanced Compute and Solutions (ACS) Business as a HP Distinguished Technologist. He has degrees in Mechanical Engineering and Physics from Bucknell University. Among his roles in ACS is Structured Innovation Lead for R&D, where he facilitates their organization-wide Friday Morning Innovation sessions. He is also ACS’s Patent Technical Coordinator. His innovative work product has included crucial inventions in products like HP Z Captis, HP MediaSmart Home Server, HP digital EO pen technologies, Iomega Zip, Jaz, Floptical & Clik! data storage drives, Identi-Key machine vision for retail key blank recognition, and AO-DVD subwavelength optical data storage, among others. Thomas has been with HP 18 years and with more than 100 U.S. Patents, has been around the IP (Intellectual Property) horn a few times. Outside of work and inventing things, he enjoys hiking with his family, reading, watching select sports, and a good Will Ferrell movie here and there.