An ultrafast all-optical switch based on nonlinear photonics?

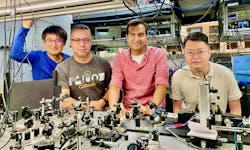

A team of Caltech engineers led by Alireza Marandi, an assistant professor of electrical engineering and applied physics at Caltech, created an all-optical switch that may enable ultrafast data processing via photons (see Fig. 1).

Unlike electronics, optics still lack efficiency in components required for computing and signal processing—and it’s a major barrier to achieving the potential of optics for ultrafast and efficient computing methods.

“During the past few decades, substantial efforts were dedicated to developing all-optical switches that could address this challenge but most of the energy-efficient designs suffered from slow switching times, mainly because they either used high-Q resonators or carrier-based nonlinearities,” says Marandi.

His team’s goal was to use the inherent parametric nonlinearity of lithium niobate, which is instantaneous, to design an ultrafast switch in the ultralow energy (femtojoule) regime. Thanks to the way atoms are arranged within lithium niobate, which doesn’t occur in nature, the optical signals it produces as outputs aren’t proportional to the input signals—it’s a nonlinear crystal.

All-optical switch design

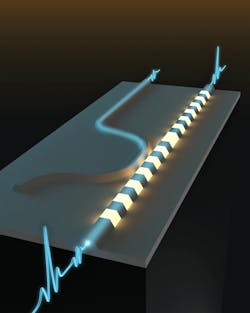

The engineers’ all-optical switch design intentionally avoids resonators, and instead relies on two other main elements for a nonlinear splitter (see Fig. 2)—and it led to the fastest all-optical switch: <50 fs, with only femtojoules of energy.First, they use the spatiotemporal confinement of light within nanowaveguides to enhance nonlinear interactions, because the strength of parametric nonlinear processes depends on the peak intensity. This spatiotemporal confinement “is possible in nanophotonic lithium niobate because of the nanoscale cross-section of the waveguides and the possibility of dispersion engineering, which allows femtosecond pulses to remain short as they propagate through the nanoscale waveguide,” says Marandi.

The second crucial element of their design is engineering quasi-phase matching for the nonlinear interactions. “We can design and change the crystallographic orientation of lithium niobate along these waveguides,” he says.

Along their nanowaveguide, they use a periodic pattern for the orientation of the crystal with a defect in the middle, which deterministically switches the nonlinear process from second-harmonic generation (SHG) to optical parametric amplification (OPA).

“By adding a wavelength-selective coupler before this defect, since low-energy input pulses don’t lead to efficient SHG in the first half of the waveguide, they will be dropped by the linear coupler,” Marandi explains. “But high-energy pulses lead to efficient SHG before the coupler, so they won’t be dropped by the coupler because the input energy will be stored in the second-harmonic wavelength of the input. After the defect, the OPA process reverts back the signal to the input wavelength.”

Integrated nonlinear photonics “provides new opportunities to rethink the device-level and system-level possibilities with photonics,” says Marandi. “Our device design is very different from previous all-optical switches, mostly because of the way we engineered the quasi-phase matching and how we can use ultrashort pulses. The resulting performance is extraordinary.”

Turns out, this is one of the most optimal ways to realize a nonlinear optical splitter. “But we’re not used to thinking about information processing in this fashion,” he says. “For instance, for communication, the most widely used way of packing information on optical signals is wavelength-division multiplexing, which isn’t really compatible with this switching mechanism.”

The switch is, however, well suited for time-division multiplexing, and the addition of such an all-optical switching mechanism may open up unprecedented avenues for time-multiplexed information processing and computing architectures to take advantage of the unique benefit of optics: ultrahigh speed. Information processing with terahertz clock rates may be one of the switch’s most important implications.

Energy efficiency

The switching energy of this device is on the order of the switching energy of transistors in the 1990s (Intel Pentium CPUs). “I wasn’t expecting the energy efficiency of the device to be so close to electronics,” says Marandi. “But the switching bandwidth is several orders of magnitude higher than the fastest transistors today.”

Since the building blocks of optical computing are already showing impressive performances, it begs the question: How can we make a system out of them with a competitive computing performance? Most likely not with the same architecture as electronic PCs.

“The possibilities in ultrafast lithium niobate nanophotonics are overwhelming,” says Marandi. “While we continue developing devices and functionalities with extraordinary performances, we’re extremely excited about building the foundation of large-scale ultrafast nanophotonic circuits and systems.”

Marandi’s group is also excited about using their nonlinear splitter as the core of an integrated mode-locked laser. “The splitter can act as a ‘saturable absorber,’ which is the main building block for passive mode locking and has been challenging to achieve in integrated photonics,” he says. “The effective saturable adsorption in our device has an extraordinary speed and energy, and its design is compatible with integrated lasers.”

RELATED READING

Q. Guo et al., Nat. Photon., 16, 625–631 (2022); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01044-5.

Sally Cole Johnson | Editor in Chief

Sally Cole Johnson, Laser Focus World’s editor in chief, is a science and technology journalist who specializes in physics and semiconductors. She wrote for the American Institute of Physics for more than 15 years, complexity for the Santa Fe Institute, and theoretical physics and neuroscience for the Kavli Foundation.